Finding a Translation: Through Helen and High Water

For my next research assignment, I was given the task of researching and locating the translatio of a saint not directly discussed in class. After reading through the indexes of both Geary’s Furta Sacra and Bartlett’s Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things?, I landed on the story of Saint Helen Imperatrix, also known as Sancta Helena Augusta. Helena was the mother of Emperor Constantine, the (supposed) Christian converter of the Roman Empire. Moreover, she remembered for her own pilgrimages and the relics that she procured in the Holy Land — most notably, the True Cross. Thus, St. Helena is a greatly studied figure for her connection to her son as well as her generosity to the Church. She is venerated not only in the Roman Catholic Church, but also the Anglican Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, and other denominations.

For clarity, I shall refer to her as St. Helena henceforth, as there are multiple Saint Helens and Helenas, but her additional title of Augusta, bestowed upon her by her son during her lifetime, distinguishes her.

Geary describes Helena’s translation thus: “In the 840’s a monk of Hautvilliers goes to Rome and secretly removes the body of Helen and re- turns to his monastery with it.”

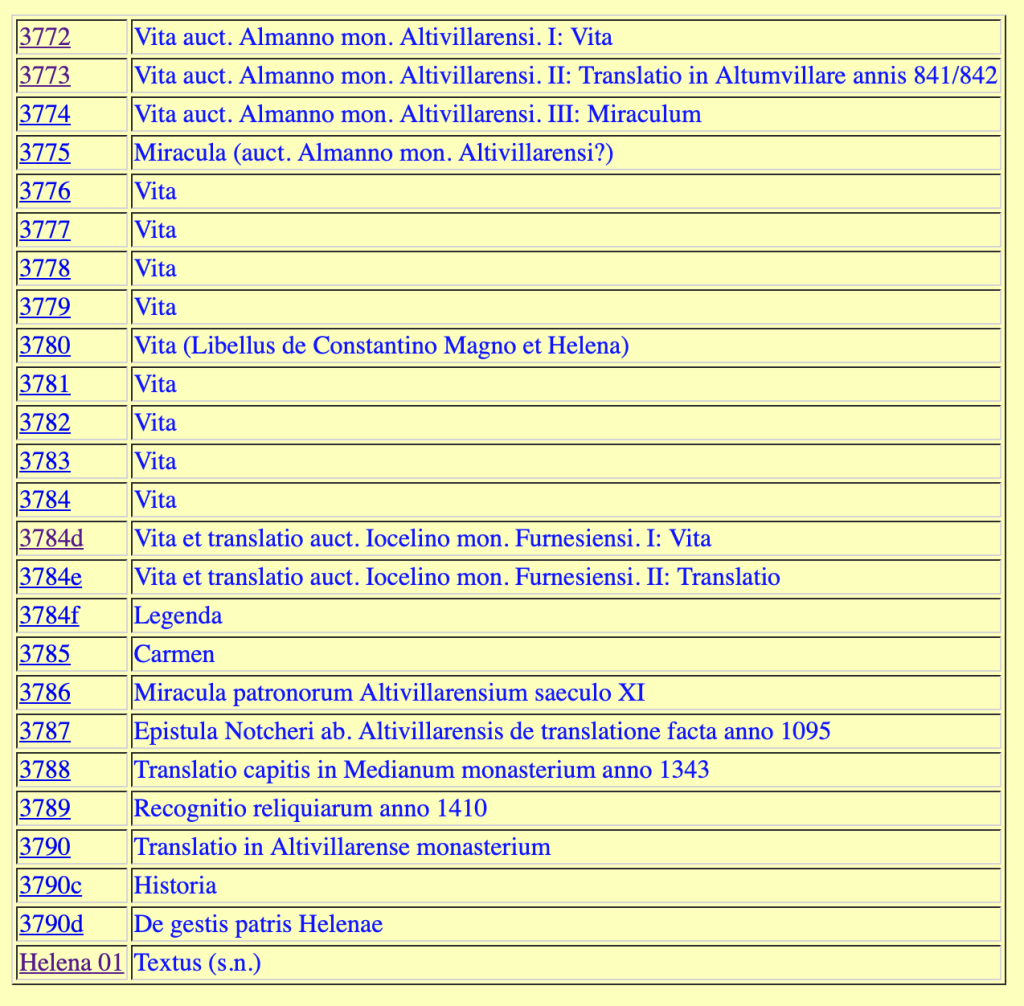

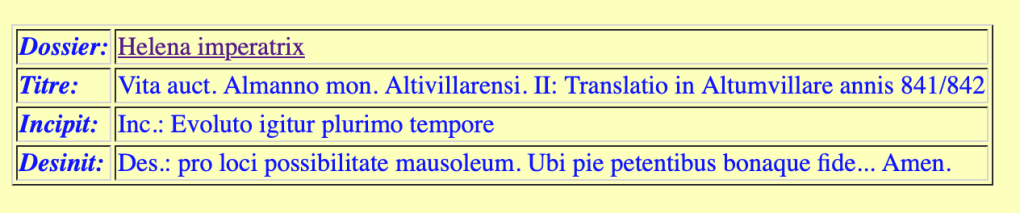

Using the BHL, I located the earliest texts of Helena’s life and her translatio to Hautvilliers, though there are later accounts of different translatios however.

The most pertinent entry was thus:

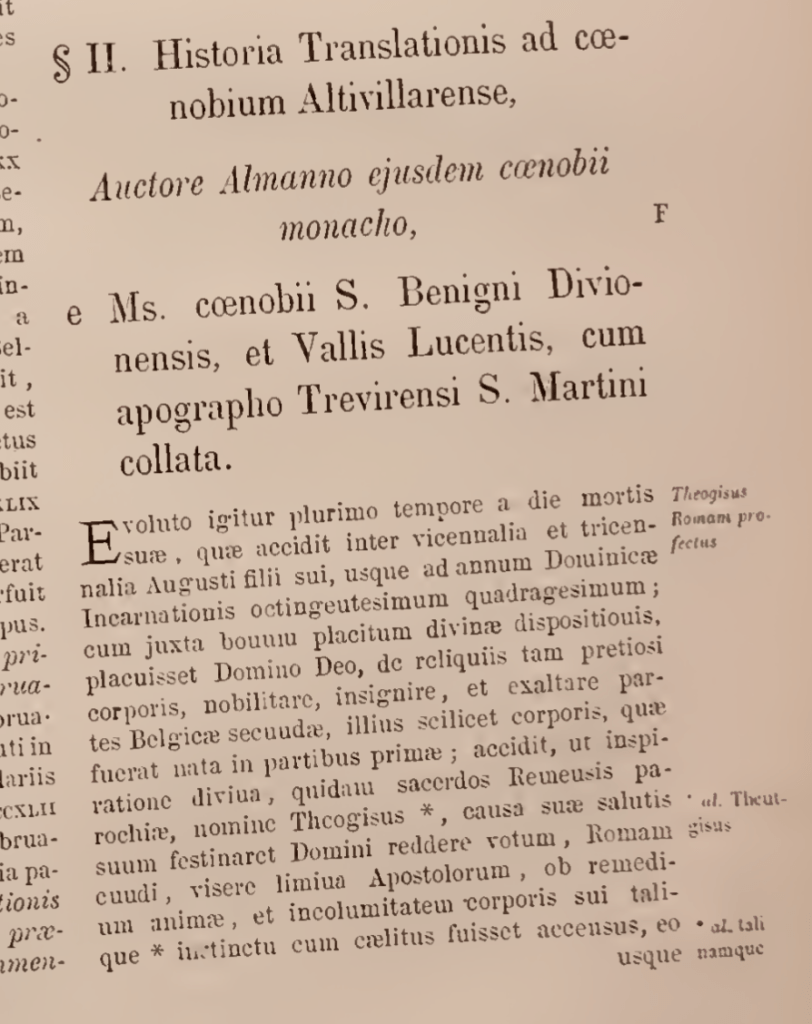

Using the reference provided by Geary and the information about the text’s author, Almannus (sometimes written as Alman or Altman in other texts), I sought to locate the translatio account in the Acta Sanctorum.

I located Helena’s entry in the third volume of the month of August in the AASS. Her feast day is August 18th, and her entry is very long. The first translatio account alone comprises eleven pages, with the rest of her entry totally more than 100 pages. Regrettably, I was not able to find an English translation of the original translatio account by Almannus. My attempts to find an unbroken piece of text to effectively translate was also moot, despite forays into Spanish, French, and Latin studies on the text.

Here, I include a picture of the beginning of the translatio — note the authorship!

Even so, despite defeat, in my research to find the original text in a translation that I could work with, a later account by Jocelin of Furness. His account, according to specialists on the topic of Helena (see bottom of page), is near to Almmanus’ account, and likely based on a secondary account which summarized Almmanus’ text. This text, which also includes Jocelin’s vita of Helena, was translated by Ingrid Sperber and Clare Downham as part of a larger project entitled “Hagiography at the Fronteirs: Jocelin of Furness and Insular Projects” by the University of Liverpool, in partnership with Dr Fiona Edmonds (University of Lancaster).

I located a free download of this translation at: https://www.academia.edu/33574268/English_translation_of_the_Latin_Life_of_St._Helena_of_Britain_by_Jocelin_of_Furness

A Summary of the Translation (of the Translation’s Summation)

Constantine had buried his mother, St. Helena, in a mausoleum beneath the church dedicated to the martyrs Marcellus and Peter in Rome, a basilica whose building she had funded.

Centuries later, in the 840s, a priest named Theogisus from Rheims travelled to Rome on a pilgrimage to visit the holy places, sacred relics, and pray. At this time, Rome was decaying — fraught with disaster, disease, and demolition. It was only fit that other lands, including France, received many relics from Rome. Thus, noting the city around him during his visit, Theogisus was inspired to go to the church where St. Helena’s body lay and take her relics to translate them back to France. He shared his plan with those he trusted, and they approved.

Then, in the night, he hid in the church with an accomplice, and together they opened the tomb and removed the saint’s body. He placed her remains in a chest which he had already set aside for this purpose, then returned the tomb to the way it was before. He then fled with his companions to return to France.

They spent the night in the forest near the town of Sutri. In the morning, one of Theogisus’ companions, a young man, attempted to lift the chest of relics onto a donkey’s back for travel, but he was unable to move it. The priest, however, was able to lift it easily. The young man was not because he was unclean due to a nocturnal emission. Though an involuntary event, the sacred body of Helena refused to be handled by the unclean young man, providing an example of sanctity and purity. The group then journeyed onward.

Next they came to a fast-flowing river called Thames (translator’s note: The River Taro, now known as Thérain, west of Reims is probably the one referenced her). The group was afraid of attempting to cross the river, but while they stood on the riverbank considering the task, the donkey carrying the sacred chest entered the river and swam straight across. The donkey was smaller than the others, but the water did not reach its flanks or its sacred burden. However, when the priest crossed on his much larger donkey, it was almost completely submerged in the raging river.

Later on the road, many people joined them in their journey, including a certain girl. While traveling down a ridge in the Alps, she slipped in a steep place. Her companions called out to Helena to save her as she fell, and the girl stopped in her tumbling. Fastenings and ropes were lowered, and the girl was lifted to safety, unharmed. The travelers glorified the holy woman of God, and their devotion showed them ready to carry the relics. One man lifted the relics onto his own horse, which he dismounted and led. When they came to descend another steep and icy portion of the mountain, he took the burden on himself to guard the chest. He stumbled and fell, but he did not drop the relics. The crowd called out to Helena, and a shocking thing occurred: his horse followed after him, embracing the man with his front legs and hooves. The horse stood, holding the man up (by Helena’s help) until men from below arrived to rescue them from the ice and rocks.

They then reached the village of Falaise, where they placed Helena’s body in the church there. A lunatic then entered the basilica, distraught and troubled, and the patrons present prayed for his healing. The saint healed him, and he was calmed. In the same village, a man who had been bedridden for fifteen years was healed after he was brought to visit the saint.

These and many other miracles occurred in Falaise and in Hautvilliers, where Helena’s translation was completed. For example, a woman who had been lame from birth was healed, jumping up and praising the saint before going on to become a nun. Another woman who had suffered paralysis in her tongue and right hand was cured by presenting a linen cloth and touching the case of the relics. A man who was deaf from birth stood during Mass in the church and heard the Gospel for the first time, his hearing returned. Also a man whose infant son was dying prayed for his healing, and he was brought back from the brink. A paralytic, who had been healed before but relapsed into sin, was brought to the church from the territory of the Treveri. He confessed his sins and was healed forever.

More were cured — paralytics, the blind, lepers. These miracles came to the Abbey of Hauviller because of Helena’s presence. Even so, some doubted the validity of the relics. With prayer and fasting for three days, the Lord revealed to the brothers that the body was true in a threefold-revelation. The relics were also confirmed by the brothers that travelled to Rome and confirmed the story, bringing back the body of the Bishop Polycarp and St. Sebastian in addition to their report.

When the saint’s feast day neared, the fisherman of the monastery insisted on fishing at night, but were unsuccessful. They invoked Helena because of their weariness, and their prayers were answered when they pulled two pikes up in their nets. One escaped back into the river, but after calling out the Helena once more, that same fish jumped from the deep water and latched onto the net, allowing the fisherman to catch it as well.

Thus concludes the abridged translatio of Helena Augusta to Hautvilliers and her related miracles.

Tertiary Sources

Birkett, Helen. “Compiling Female Sanctity: The Sources for the Vita S. Helenae.” In The Saints’ Lives of Jocelin of Furness: Hagiography, Patronage and Ecclesiastical Politics, 59-84. Woodbridge, Suffolk; Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer, 2010. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt14brt3x.8?refreqid=excelsior%3Aedcfc497065071b28c162272b73d50ed&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Drijvers, Jan Willem. “Trier and Rome.” In Helena Augusta: The Mother of Constantine the Great and the Legend of Her Finding the True Cross, 21-34. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 2010. Found on Google Books at https://books.google.com/books?id=50ZmimTfp0YC&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=translation+of+st+helen+to+hautviller&source=bl&ots=jg1RQE05st&sig=ACfU3U2187Y_P54o8VDMFcZCNixcPGyjcA&hl=en&ppis=_e&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiO6t_h3Y3oAhVBXK0KHZOFBVcQ6AEwD3oECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

Harbus, Antonina. “Helena in Trier and Hautvilliers.” In Helena of Britain in Medieval Legend, 44-47, 50-51. Cambridge, UK: D. S. Brewer, 2002. Found on Google Books at https://books.google.com/books?id=6uK4VHOYVHEC&pg=PA47&lpg=PA47&dq=vita+helenae+altmann&source=bl&ots=bI_Uwmo_wS&sig=ACfU3U2tzNTTSfNg-97iqJXDUqmThWoeTg&hl=en&ppis=_e&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjntdKx9Y3oAhUJTN8KHYPZDCEQ6AEwAXoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=vita%20helenae%20altmann&f=false