For this assignment, I have chosen St. Agnes, not only because I am most familiar with the story of her martyrdom, but also because her canonization and thus widespread veneration. Though Agnes does not have a cult in the same manner that many other saints do, she has still inspired many artist to immortalize her their depictions.

Because this article will be focused on Agnes’ depictions, please view my earlier posts for a more complete summary of Agnes’ martyrdom. Below I will attempt to illustrate the common themes found in images of Agnes through these images. Their sources I will include.

An Incomplete Timeline of Examples

The earliest piece of artwork that I could locate dates back to the sixth century.

This image is taken from a large mosaic on the left wall of the nave of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, in Ravenna. Agnes is accompanied by a lamb, a symbol that will follow her in almost every rendering I could find.

Next, I located this mosaic, which traces back to the 7th century.

Honorius is most likely the Pope on the left, pictured with a miniature of a church, because he commissioned its building.

These mosaics belong to the apse of Sant’Agnese Fouri le Mura, or Saint Ages Outside the Walls. This church is built atop the catacombs where St. Agnes’ remains are said to be housed, with the exclusion of her skull. Her (purported) skull is housed in the church of St. Agnes Agone, a 17th century church inside the city walls. Notably, this depiction does not include the most common symbol that accompanies St. Agnes, her lamb.

Unusually, I had an incredibly difficult time finding work between this period and the 14th century. Those which I did find were not of a licensure I could share, or the image was so poor that it was not worth including, as nothing could be analyzed from it. Thus, onto the next notable specimen.

In this stained glass window, originally produced c. 1340 in Carinthia, Austria, Agnes is pictured with a variation on her lamb theme which appears in several productions of her image. Here, the lamb appears as if it is on a medallion or plate, rather than in her hands. I was not able to find any reasoning besides stylistic as to why the lamb might be portrayed in this way. For lack of a better term, I shall refer to is as the “medallion of the lamb”. In her other arm, she carries the traditional palm frond that symbolizes martyrdom.

This painting has a great deal going on besides just St. Agnes, who peeks in on the left side in a pink-red robe holding a small medallion of a lamb once more. Here, all the saints portrayed carry some sort of artifact or marker which identify them as Saint John the Evangelist, Saint Agnes, Saint Peter, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Saint Lucy, Saint Paul, and Saint John the Baptist, with the exclusion of the remaining female saint that is not identified. However, I included it because it shows that once again, St. Agnes is known by her lamb.

This painting brings forth a more graphic image of the saint; this artist chose to portray the gravitas of her martyrdom. A guard draws her close to slit her throat after burning her at the stake has failed. The crowd is tumultuous. Above, angels wait with a crown for the soon-to-be martyr to welcome her into heaven. And what does she clutch close to her? Not a relic from her vita, but her identifying lamb — an artistic touch to further illustrate who this martyr is: Agnes.

This pastoral scene is one of many that depict St. Agnes in pink robes, holding her lamb in repose. It appears she is sitting amongst Roman ruins, but it is unclear if she is at peace or saddened.

This alterpiece, found in a chapel within Burgos Cathedral in Spain, dates to the 16th century. St. Agnes is depicted with a book, most likely representing Scripture. She also is unusually dressed in what would have been a period gown for 16th century Spain, but not a Roman martyr. Never fear — she is still accompanied by her token lamb.

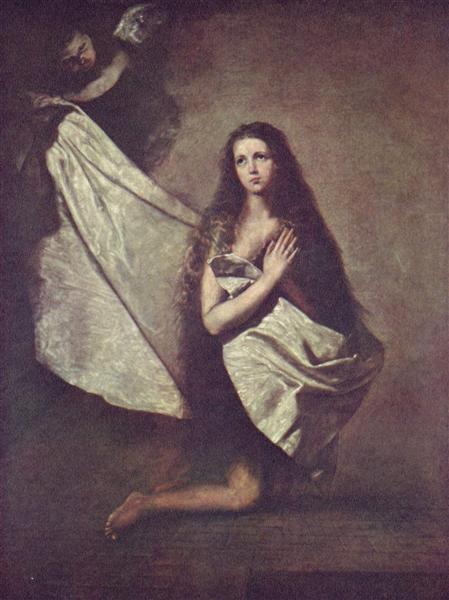

This painting depicts the darker side of Agnes’ tale once more, as well as one of her miracles. In suiting to one of the prominent versions of the account of her persecution, the painting depicts a man snatching away her covering, hoping to shame the chaste woman with nakedness. However, her hair appears to be growing, as it does in the story, covering her and preserving her modesty. This is a rare example without her lamb, but perhaps the iconic tale of her miraculous hair speaks for itself.

In this painting, St. Agnes is partly exposed by her attackers. However, rather than merely miraculously growing long hair, two angels protect and help clothe Agnes. Meanwhile, the men which had attempted to violate her flee, or, as in the case of the man on the ground, are struck down and blinded. Both the tale of the blinding and her long hair — which does appear to reach past her waist where it peaks out of the shadow of the sheet — suit the commonly accepted events of her vita.

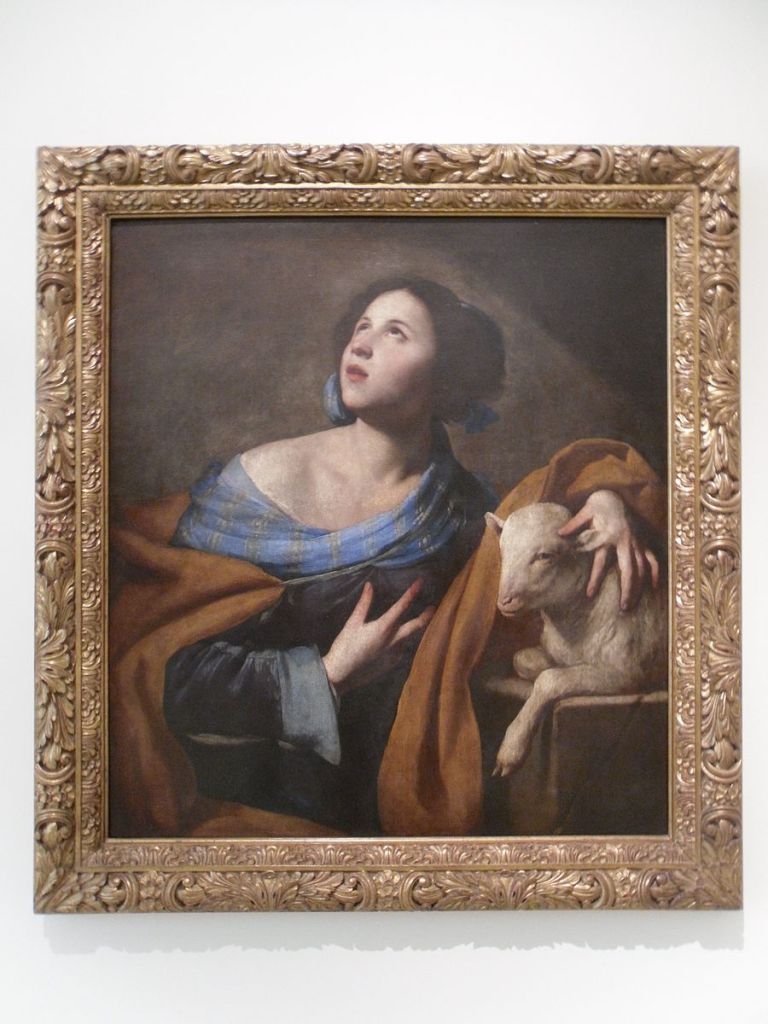

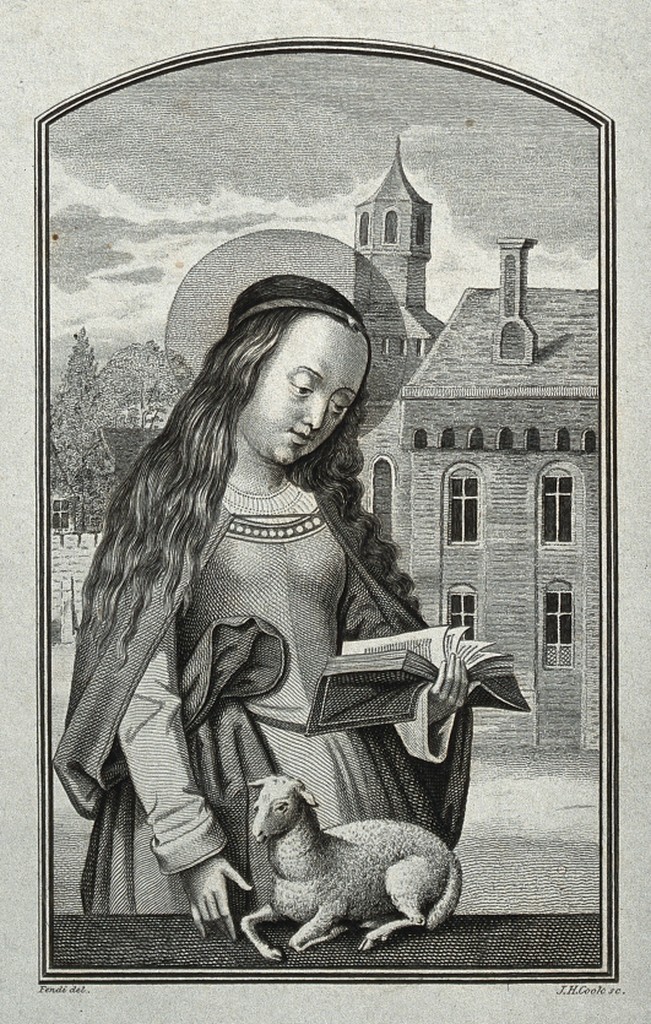

I grouped the three of these images together because with some variation, they illustrate the similarities of Agnes’ portrayal. The first, c. 1620, adds the elements of angels bestowing a crown and palm branch of martyrdom upon her. The second is more simplistic, as is the third. The second is the only one without the martyr’s palm, but all three have the continuous theme of the lamb.

This image is not ideal in quality, but I wanted to include this unique fresco. Once more, we have a portrayal of St. Agnes’ martyrdom, with many details from her legends. The man in the lower left foreground may be the one struck down and blinded. There is what appears to be charred wood in the lower right corner, most likely her failed pyre. Above Agnes, angels descend to bring her a wreathed crown, and on the right, there is also the classic editorial addition of Agnes’ lamb. What is interesting about this version is that the executioner appears to be cutting her in the side, rather than her neck, differing from the traditional account. The author of the article I found this image in posits that this is because the artist wanted to draw a parallel between her wound and the wound in Christ’s side.

To close this perusal, I wanted to provide one more “standard” St. Agnes. Here she is pictured with her lamb, as usual. She also has a book of what is mostly likely Scripture. She appears younger than in most previous renditions, and her dress is not period-appropriate for a Roman citizen at the turn of the fourth century. However, these discrepancies aside, this is a strong example of the commonality of most Agnes portrayals — peaceful, focused on holy matters, and accompanied by a lamb.

For the sake of avoiding further redundancy, I will close this foray into the art history of Saint Agnes.

Agnes Had a Little Lamb: Closing Remarks

Saint Agnes has been portrayed in several ways over the centuries, though predominantly consistent with either the stories that surround her life, or consistent with the standard combination of Agnes and her sheep.

Why is Agnes so frequently portrayed with a sheep, especially if it did not feature in any of her vitae accounts? There are a few theories. Lambs are frequently associated with purity, and she is the patron saint of chastity and young women, among others. The lamb is also a symbol closely associated with Christ, as the Lamb of God, and a symbol of sacrifice that dates back to the Old Testament. It may then harken to her sacrifice as a martyr for Christ and her closeness to Him because of her righteous devotion.

However, the predominant theory seems to be that the connection may have been drawn because of her name. The Latin word for lamb is “agnus”, which developed from the Greek ἁγνή (hagnē), meaning “chaste, pure”. Thus, the sight of the lamb would connect the viewer to the name Agnes and to her chastity, for which she was martyred.

Altogether, this has been an interesting adventure down the art history rabbit hole, and a nice time revisiting my friend, St. Agnes.

Additional Basic Info Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agnes_of_Rome

Further Tangential Reading (which did not have images I could incorporate and thus, sadly, did not fit this assignment): St Agnes of Rome as a Bride of Christ: A Northern European Phenomenon, c. 1450-1520, by Carolyn Diskant Muir